ĐỌC NGÔ THÌ NHẬM: MINH TÂM, KIẾN TÍNH

Nguyên Giác

Bài viết này sẽ phân tích một đoạn văn nói về lời dạy về minh tâm và kiến tính, ghi trong sách Trúc Lâm Tông Chỉ Nguyên Thanh, một tác phẩm về Thiền Tông Việt Nam xuất bản lần đầu vào năm 1796. Tác phẩm này được in trong Ngô Thì Nhậm Toàn Tập - Tập V, ấn hành năm 2006 tại Hà Nội, do nhiều tác giả trong Viện Nghiên Cứu Hán Nôm biên dịch.

Những lời dạy trong sách này mang phong cách Thiền Tông Việt Nam, vì ngài Ngô Thì Nhậm (1746-1803) khi rời quan trường đã xuất gia, trở thành vị sư có tên là Hải Lượng Thiền Sư, và được nhiều vị sư tôn vinh là vị Tổ Thứ Tư của Dòng Thiền Trúc Lâm.

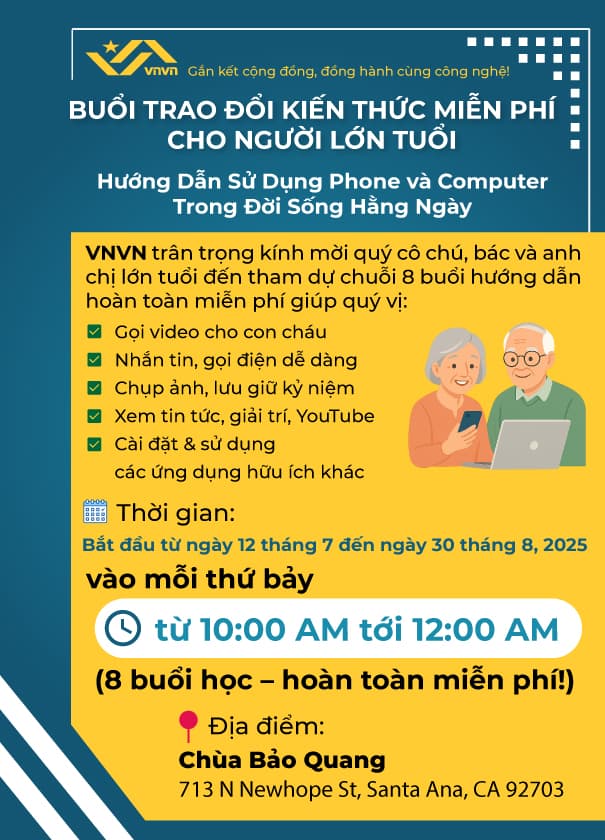

Nơi đây, chúng ta chụp lại từ bản PDF nửa cuối trang 213, và hai dòng đầu trang 214 của sách nêu trên, ghi lời vị sư tên là Hải Hòa, trích:

Đánh máy lại sẽ như sau:

“...đường xằng bậy, sa vào cái hố tội ác. Kẻ nào triển miên ân ái thì mãi mãi không tìm ra đường giải thoát; kẻ nào đắm đuối danh lợi thì đau đớn quằn quại trong vòng nước sôi lửa bỏng, luôn sống trong cảnh phiền não lo âu, vô hình chung sa xuống địa ngục, vượt không khỏi, chạy không thoát. Vì vậy Phật Thích Ca Mâu Ni rủ lòng thương xót, dạy cho người ta minh tâm, kiến tính. Khi người ta được minh tâm thì tâm vốn là hư không, khi người ta được kiến tính thì tính không dựa dẫm nữa. Trong thế gian, hết thảy mọi sự mọi vật, đều được coi là bình đẳng, tinh tiến không bao giờ lơi, thì thành được Phật đạo. Không nhơ không sạch, không thêm không bớt, lia hẳn được mọi nỗi khổ đau, đó là cái pháp môn cao bậc nhất để phá địa ngục.” (hết trích)

Tóm tắt như sau: Đức Phật dạy pháp giải thoát là hãy soi cho sáng tâm thì sẽ thấy được tính của tâm. Người xưa thường gọi tắt là Thấy Tánh, hay Thấy Tính. Lời dạy giải thích thêm rằng, khi tâm sáng rồi, sẽ thấy tâm vốn là hư không, vì như thế, tính của tâm không nương dựa bất kỳ những gì nữa. Trong cái rỗng rang, cái Tánh Không của tâm đã bật sáng, thì tất cả mọi thứ đều bình đẳng, thường trực tinh tiến quán sát như thế thì giải thoát. Pháp thấy tính này, tức là thấy cái Tánh Không đó, là soi thấy các thứ đều không có gì nhơ, không có gì sạch, không có gì thêm, không có gì bớt, lìa xa mọi khổ đau, và đây là pháp cao nhất để phá địa ngục.

Trong lịch sử Thiền Tông, chúng ta thấy một số trường hợp các vị sư nhìn vào tâm và thấy tất cả các hiện tướng trong tâm thực ra đều là Không.

Một trường hợp nổi tiếng ghi lại trong Thiền sử Trung Hoa là về nhà sư Huệ Khả (494 - 601), Sau một thời gian theo học Tổ Bồ Đề Đạt Ma, một hôm Huệ Khả tới thưa rằng: “Bạch Hoà thượng tâm con chẳng an, xin Hòa thượng dạy con pháp an tâm.”

Ngài Bồ Đề Đạt Ma nhìn vào Huệ Khả, nói: “Ngươi hãy đem tâm ngươi ra đây, ta sẽ an tâm ngươi cho.”

Ngài Huệ Khả tự nhìn vào tâm một chặp, rồi thưa: “Con tìm tâm không được.”

Tổ Bồ Đề Đạt Ma nói: “Ta đã an tâm ngươi rồi vậy.”

Từ đó, ngài Huệ Khả biết chỗ an tâm, thấy ngay nơi tâm vắng bặt các phiền não, xa lìa tham sân si.

Trở lại cuốn sách của ngài Ngô Thì Nhậm, chúng ta thấy rằng người tu hãy quán sát tâm để thấy Tánh Không của tâm, thì không còn gì để nương tựa, và tâm đó thì không nhơ, không sạch. Thiền Tông cũng từng có câu nói rằng: “Khi đất tâm trở về Tánh Không, thì mặt trời trí tuệ sẽ chiếu sáng.”

Cổ đức khi nói về tâm này, cũng nói rằng nơi đây, không còn Phật và cũng không còn Ma nữa. Có nghĩa là, nơi tâm của giải thoát không còn vướng vào bất kỳ sắc, thọ, tưởng, hành, thức nào nữa. Chư tổ thường dạy cách vào bằng tánh nghe. Bạn thử chú tâm vào tiếng chim kêu, hay chú tâm nghe bất kỳ một ca khúc nào, bạn sẽ thấy trong cái được nghe hiển nhiên nó phải là Không, nên nó liên tục biến mất, vừa sanh là liền diệt, trong khi bạn nghe thì bạn một cách tự nhiên vô niệm, vì bạn không bám víu gì.

Hễ bạn đang nghe mà nghĩ ngợi, thì bạn sẽ mất đi cái thực tại ở đây và bây giờ. Đó cũng là cái tâm Không của vô niệm. Đó cũng là lời Đức Phật dạy ngài Bahiya rằng hãy để cái được nghe là cái được nghe, và hãy để cái được thấy là cái được thấy, thì ngay đó là giải thoát. Không cần tu, không cần mài giũa gì nơi cái đang thấy và cái đang nghe đó, vì tự thân tâm bạn phải là Không, thì mới hiển lộ được những cái được nghe, cái được thấy.

Nếu bạn thấy khó nhận ra cái Tánh Không của tâm, thì bạn có thể quán sát theo nhiều lời Đức Phật dạy. Đức Phật dạy trong Kinh SA 265 rằng người tu hãy quán sát sắc như bọt nước, hãy quán sát thọ như bong bóng nước, hãy quán sát tưởng như quáng nắng xuân, hãy quán sát các hành như thân cây chuối và hãy quán sát thức như trò huyễn ảo. Như thế sẽ thấy tất cả không thật, không hề có cái gì gọi là cái tôi, hay cái của tôi.

Trong Kinh SA 335, Đức Phật dạy bài Kinh về Đệ nhất nghĩa không. Ngài nói rằng các pháp liên tục biến đổi theo vô lượng duyên mà hiện ra rồi biến mất, thấy liên tục như thế là sẽ thoát khổ, vì không còn bám víu gì nữa trong ba cõi, sáu đường. Kinh SA 335, bản dịch của hai thầy Tuệ Sỹ và Đức Thắng như sau, trích:

“Thế nào là kinh Đệ nhất nghĩa không? Này các Tỳ-kheo, khi mắt sanh thì nó không có chỗ đến; lúc diệt thì nó không có chỗ đi. Như vậy mắt chẳng thật sanh, sanh rồi diệt mất; có nghiệp báo mà không tác giả. Ấm này diệt rồi, ấm khác tương tục, trừ pháp tục số. Đối với tai, mũi, lưỡi, thân, ý cũng nói như vậy, trừ pháp tục số.

“Pháp tục số, tức là nói, cái này có thì cái kia có, cái này khởi thì cái kia khởi, như vô minh duyên hành, hành duyên thức, nói chi tiết đầy đủ cho đến thuần một khối khổ lớn tập khởi. Lại nữa, cái này không thì cái kia không, cái này diệt thì cái kia diệt, vô minh diệt nên hành diệt, hành diệt nên thức diệt. Như vậy, nói rộng cho đến thuần một khối khổ lớn tụ diệt. Này các Tỳ-kheo, đó gọi là kinh Đệ nhất nghĩa không.”

Kinh SA 301 do Đức Phật dạy cũng chỉ rõ về Tánh Không của các pháp. Kinh này gợi nhớ tới bài Bát Nhã Tâm Kinh, nơi thực tướng là Tánh Không, nhưng không có nghĩa là cái không của hư vô luận, cũng không phải là cái có của thường hằng luận. Nơi thực tướng Không là nơi dung chứa tất cả thế giới này một cách bình đẳng. Y hệt như nước biển dung chứa tất cả các bọt nước, chỉ vào bọt nước thì nói là Không, chỉ vào tánh ướt thì nói là Có, chỉ vào trung đạo thì không có lời nào để nói nữa.

Kinh SA 301 ghi rằng, sau khi nghe Đức Phật dạy xong, ngài Ca-chiên-diên tức khắc trở thành A La Hán, xa lìa tất cả tham sân si. Bản dịch của hai Thầy Tuệ Sỹ và Đức Thắng trích như sau:

“Phật bảo Tán-đà Ca-chiên-diên: ‘Thế gian có hai sở y, hoặc có hoặc không, bị xúc chạm bởi thủ. Do bị xúc chạm bởi thủ nên hoặc y có hoặc y không. Nếu không có chấp thủ này vốn là kết sử hệ lụy của tâm và cảnh; nếu không thủ, không trụ, không còn chấp ngã, thì khi khổ sanh là sanh, khổ diệt là diệt, đối với việc này không nghi, không hoặc, không do người khác mà tự biết; đó gọi là chánh kiến. Đó gọi là chánh kiến do Như Lai thi thiết. Vì sao? Thế gian tập khởi, bằng chánh trí mà quán sát như thật, thì thế gian này không phải là không. Thế gian diệt, bằng chánh trí mà thấy như thật, thế gian này không phải là có. Đó gọi là lìa hai bên, nói pháp theo Trung đạo. Nghĩa là, ‘Cái này có nên cái kia có, cái này khởi nên cái kia khởi; tức là, duyên vô minh nên có hành,… cho đến, thuần một khối khổ lớn. Do vô minh diệt nên hành diệt,… cho đến, thuần một khối khổ lớn diệt.’”

Phật nói kinh này xong, Tôn giả Tán-đà Ca-chiên-diên nghe những gì Phật đã dạy, chẳng khởi các lậu, tâm được giải thoát, thành A-la-hán.”

Đối chiếu với lời Đức Phật dạy trong các kinh dẫn trên, chúng ta thấy rằng Thiền Tông Việt Nam với các lời dạy trong sách Trúc Lâm Tông Chỉ Nguyên Thanh là pháp trực chỉ, không mượn bất kỳ phương tiện nào, chỉ thẳng vào thực tướng của tâm là Tánh Không, nơi đó sẽ không còn gì bám víu được. Người tu chỉ cần bảo nhậm cái thấy và cái nghe thường trực đó, nơi đó các pháp tự hiển lộ tánh vô thường, vô ngã, hư ảo không ngừng. Nơi đó, không có lời để nói, vì ngôn ngữ là kết quả của những cái hôm qua, trong khi tất cả những cái thấy, cái nghe của người tu là thường trực tự làm mới không ngừng.

.... o ....

Reading Ngô Thì Nhậm: Enlighten the mind and perceive its essence

Written and translated by Nguyên Giác

This article will analyze a passage about the teachings on enlightening the mind and perceiving its essence, as recorded in the book Trúc Lâm Tông Chỉ Nguyên Thanh, a significant work on Vietnamese Zen Buddhism first published in 1796. This text was printed in "Ngô Thì Nhậm Toàn Tập - Tập V", published in 2006 in Hanoi, and has been translated by various authors from the Viện Nghiên Cứu Hán Nôm.

The teachings in this book reflect the principles of Vietnamese Zen Buddhism. After leaving his official position, Ngô Thì Nhậm (1746-1803) became a monk known as Hải Lượng Thiền Sư and was revered by many as the Fourth Patriarch of the Trúc Lâm Zen Sect.

Here, we capture an image from the PDF version of the latter half of page 213 and the first two lines of page 214 of the aforementioned book, documenting the words of the monk named Hải Hòa.

It would appear as follows: “...the path of confusion, falling into the pit of sin. Those who indulge in lust will never find a path to liberation; those who chase fame and fortune will suffer in the molten waters, perpetually living in a state of anxiety and worry, unconsciously descending into hell, unable to escape. Therefore, Buddha Shakyamuni, out of compassion, taught people to enlighten their minds and to perceive the essence of their thoughts. When one achieves enlightenment, the mind is initially empty. In this state, there is no reliance on anything. In the realm of existence, all things are regarded as equal in the emptiness of the mind. If one remains diligent in their efforts, they will attain Buddhahood. Within the essence of a mind that is empty, there is neither defilement nor purity, neither increase nor decrease. All suffering can be entirely eradicated. This represents the highest method for transcending hell." (end of quote)

We can summarize the teachings as follows: The Buddha taught that the method of liberation involves illuminating the mind to understand its true nature. The ancients often referred to this as perceiving the essence of the mind. The teachings further explain that when the mind is enlightened, it becomes evident that the mind is inherently empty. This realization indicates that the nature of the mind does not depend on anything external. In the illuminated emptiness of the mind, all things are equal. By consistently observing this state with diligence, one can attain liberation. The method of perceiving this nature—recognizing that emptiness—reveals that all things are neither dirty nor clean, neither added to nor diminished, and are free from all suffering. This understanding represents the highest path to transcending hell.

In the history of Zen, there are numerous instances where monks examined their minds and realized that all the thoughts and images within were, in fact, manifestations of emptiness.

A famous case recorded in Chinese Zen history involves the monk Hui Ke (494-601). After studying with Bodhidharma for some time, Hui Ke approached him one day and said, "Venerable Sir, my mind is not at peace. Please teach me the method to calm my mind."

Bodhidharma looked at Hui Ke and said, “Bring your mind here, and I will calm it.”

Huike contemplated for a moment and then said, “I cannot find my mind.”

Bodhidharma stated, “I have already calmed your mind.”

From that moment on, Huike understood how to calm his mind and immediately recognized that it was free from afflictions, distant from greed, anger, and ignorance.

Returning to the work of Ngô Thì Nhậm, we find that the practitioner should observe the mind in order to perceive its emptiness. In this state, there is nothing to cling to, and the mind is neither tainted nor pure. The Zen tradition also states, "When the mind's foundation returns to emptiness, the sun of wisdom will shine."

When the ancients spoke of the mind, they asserted that in this state, there is neither Buddha nor Mara. In other words, within the mind of liberation, there is no entanglement with any form, feeling, perception, action, or consciousness. The patriarchs often taught how to enter this state through the nature of hearing. Try focusing on the sound of a bird chirping or listening to any song. As it continuously fades away, you will notice that what you hear is, in essence, emptiness. As soon as a sound is born, it immediately ceases to exist. While you are listening, your mind becomes naturally thoughtless, as you would not cling to anything else.

Whenever you listen and think, you may lose touch with the present moment. This state reflects the emptiness of no-thought. It aligns with the teachings of the Buddha to Bahiya: allow what is heard to be simply what is heard, and permit what is seen to be merely what is seen; in doing so, liberation is found. There is no need for practice or to refine anything in the act of seeing and hearing, for your own mind must embody emptiness. Only then can what is heard and what is seen be fully revealed.

If you find it challenging to grasp the concept of the mind's emptiness, you can reflect on various teachings of the Buddha. In Sutta SA 265, the Buddha instructs practitioners to contemplate form as foam, feelings as bubbles, perceptions as a ray of sunlight in spring, formations as banana tree trunks, and consciousness as an illusion. By doing so, you will come to understand that everything is transient and that the notions of self and possession are ultimately illusory.

In the SA 335 Sutra, the Buddha teaches about the ultimate truth of emptiness. He explains that all dharmas are in a state of constant change, influenced by countless causes and conditions, appearing and disappearing. Recognizing this continuous flux allows one to be free from suffering, as it eliminates attachment to anything within the three realms and six paths. The SA 335 Sutra, translated by Choong Mun-keat, is as follows:

“What is the discourse on emptiness in its ultimate meaning?

“Monks, when the eye arises, there is no place from which it comes; when it ceases, there is no place to which it goes. Thus, the eye, being not real, arises; having arisen it ceases completely. It is a result of previous action but it has no doer.

“When these aggregates cease, other aggregates continue, with the exception of this transient dharma. It is the same with the ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind. They are exceptions to the transient dharma.

“The meaning of transient dharma is: Because this exists, that exists; because this arises, that arises, thus: Conditioned by ignorance are activities; conditioned by activities is consciousness, and so on … and thus arises this whole mass of suffering.

“And again, when this does not exist, that does not exist; when this ceases, that ceases. When ignorance ceases, activities cease; when activities cease, consciousness ceases, and so on …, and thus ceases this whole mass of suffering.

“Monks, this is called the discourse on emptiness in its ultimate meaning.”

.

The SA 301 Sutra, taught by the Buddha, clearly emphasizes the Emptiness of all dharmas. This sutra serves as a reminder of the Heart Sutra, which reveals that the true nature of reality is Emptiness. However, this does not imply a nihilistic void or the affirmation of eternalism. The true essence of Emptiness encompasses all aspects of the world equally. Just as the ocean contains countless bubbles, pointing to the bubbles represents Emptiness, while acknowledging the wet nature of the ocean signifies Existence. The middle way transcends these distinctions, leaving little more to be said.

The SA 301 Sutra records that, after listening to the Buddha's teachings, Katyāyana instantly attained Arahantship, becoming free from all greed, anger, and delusion. Choong Mun-keat's translation reads as follows:

“The Buddha said to Katyāyana: “There are two bases to which people in the world are attached, to which they adhere: existence and non-existence. Because of their attachment and adherence, they are based on either existence or non-existence.

“In one who has no such attachment, bondage to the mental realm, there is no attachment to self, no dwelling in or setting store by self. Then, when suffering arises, it arises; and when it ceases, it ceases.

“If one does not doubt this, is not perplexed by it, if one knows it in oneself and not from others, this is called right view right view as established by the Tathāgata (the Buddha).

“Why is this? One who rightly sees and knows, as it really is, the arising of the world, does not hold to the non-existence of the world. One who rightly sees and knows, as it really is, the cessation (passing away) of the world, does not hold to the existence of the world.

“That is called avoiding the two extremes, and teaching the middle way, namely: Because this exists, that exists; because this arises, that arises. That is, conditioned by ignorance, activities arise, and so on …, and thus this whole mass of suffering arises. When ignorance ceases, activities cease, and so on …, and thus this whole mass of suffering ceases.”

When the Buddha had taught this discourse, the venerable Katyāyana, having heard what the Buddha had said, became freed of all influences, attained liberation of mind, and became an arahant.”

When comparing the Buddha's teachings in the aforementioned sutras, we observe that Vietnamese Zen, as presented in the book Trúc Lâm Tông Chỉ Nguyên Thanh, is a direct method that does not rely on any intermediaries. This approach points directly to the true nature of the mind, which is emptiness—an essence devoid of anything to cling to. The practitioner need only maintain a constant awareness of seeing and hearing, allowing the dharmas to naturally reveal their impermanent, non-self, and illusory nature without interruption. In this state, words become unnecessary, as language is merely a product of past experiences, while the practitioner's perception of seeing and hearing remains constant and continually renews itself.

.

THAM KHẢO / REFERENCE:

-- Kinh SA 265:

https://suttacentral.net/sa265/vi/tue_sy-thang

https://suttacentral.net/sa265/en/analayo

-- Kinh SA 335:

https://suttacentral.net/sa335/vi/tue_sy-thang

https://suttacentral.net/sa335/en/choong

-- Kinh SA 301:

https://suttacentral.net/sa301/vi/tue_sy-thang

https://suttacentral.net/sa301/en/choong

Đọc thêm:

Ngô Thì Nhậm Toàn Tập Tập 5 (PDF)